How do bones function and what are they made of?

How do bones function and what are they made of?

Bones and their function

The human body is composed of multiple specialized tissue types. Each with unique properties which are tailored to support the different functions throughout the body. One such tissue is our bones, which most of us would characterize as rigid, calcified structures that form the skeleton. Besides providing structure and stability to our bodies, the skeleton also functions as a stem cell niche and a reservoir for inorganic ions.

Figure 1: Illustration of the cell types within bone

Bone is composed of a dynamic, mineralized connective tissue. The tissue provide the ability to fulfill its function as a skeleton for the body. The organization and components of the bone tissue account for the stability of the bones. The strength of the bone can be determined by comparing the turnover, bone amount, bone architecture, and the properties of the bone matrix.

Bone is compartmentalized into bone matrix and bone marrow. The bone matrix provides mechanical support while bone marrow functions, among other things, as a stem cell niche.

The main components of the inorganic and organic phases of the bone matrix are inorganic hydroxyapatite crystals, organic collagen, and non-collagenous protein. The inorganic phase also contains sodium, potassium, fluorite, zinc, barium, citrate, magnesium, bicarbonate, carbonate, and strontium.

Collagen is embedded in connective tissue such as skin and muscle and contributes to the strength of these tissues due to the architecture of collagen. The strength and stiffness of bone are in part due to the collagen maturation, orientation of collagen fibers, and the integration of collagen in the mineral matrix. Collagen provides the bone with a much-needed elasticity to withstand the compressions that the bones are exposed to. The integration of collagen in hydroxyapatite crystals segregate bone from other connective tissue as the collagen fibers and hydroxyapatite crystals are orientated in the same direction in a process called calcification of bone.

What cell types exist within bone?

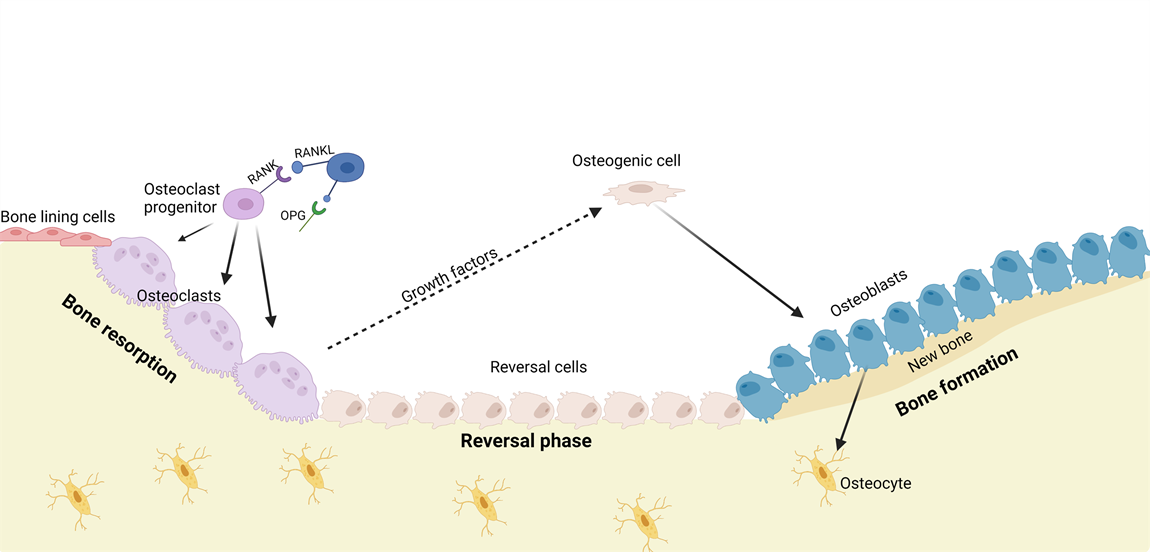

A great variety of cell types, such as osteoblasts, osteoclasts, osteocytes, and reversal cells, are located in bone. Where some are responsible for making new bone. Others are removing old bone or taking care of bone health in other ways. Osteoblasts are bone forming cells and arise from differentiation of early osteoblast progenitors, normally referred to as osteogenic cells. The osteoblasts are capable of producing the collagen-rich extracellular matrix and subsequently depositing calcium on the collagen fibers, thereby creating new mineralized bone [4-6].

Osteoclasts are the counter opposites of osteoblasts. Their key responsibility is to resorb bone through the production of proteolytic enzymes and secretion of hydrogen ions. This process releases skeletal minerals and is vital for managing the extracellular calcium activity. It furthermore allows soled skeletal structures to be replaced by a hollower skeletal architecture with a better strength-to-weight ratio [3,4,7,8]. Osteocytes are terminally differentiated osteoblasts integrated in the bone matrix, sensing the structural integrity and inflammation of bone. They are responsible for initiating the bone remodeling process when needed [4,9,10]. Lastly, the reversal cells remove matrix debris and produce the coupling signal between resorption and formation of bone [4,7,11].

Bone remodeling

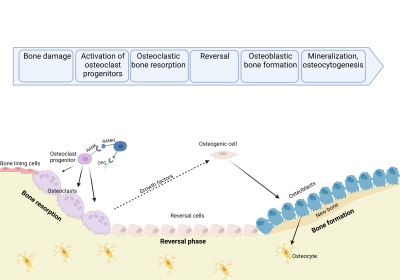

The maintenance of bone is done by bone remodeling. This is a process that removes injured bone matrix and creates new mineralized bone. This is also a vital part of keeping the homeostasis of inorganic ion serum levels [4,7,8]. Remodeling signals like low serum Ca2+, low levels of Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) and low levels of Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β) initiates the bone replacement by increasing osteoclastogenesis [4,7,8].

PTH induces osteoclast recruitment and differentiation through binding to the PTH-receptor on osteoblastic cells which activates numerous intracellular pathways and changes the expression of Macrophage Colony‐Stimulating Factor (M-CSF), Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κ-B Ligand (RANKL), and Osteoprotegerin (OPG) [3,4,9,12]. Increased levels of M-CSF and RANKL promote proliferation, differentiation, and fusion of osteoclast precursors into active osteoclasts and acts as chemoattractants for osteoclast precursors to the resorption site.

Active osteoclasts form an isolated environment and degrade bone matrix by releasing hydrogen ions and collagenolytic enzymes [4,7,8,12]. Programmed cell death of osteoclasts ends the bone resorption followed by reversal cells cleaning and preparing the exposed bone before formation of new bone matrix [4, 7]. Signals released from the bone matrix during bone resorption such as Insulin-like Growth Factor-I and -II, TGF-β, and Bone Morphogenetic Proteins initiate bone formation [4,8,10,12]. Recruiting and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells or early osteoblast progenitors to the exposed bone initiates bone formation. Mature osteoblasts produce unmineralized bone consisting of type I collagen, proteoglycans, and glycosylated proteins followed by calcification of bone by inserting hydroxyapatite into the unmineralized bone [4,7,8]. The bone formation is completed when the resorbed bone matrix is replaced with new calcified bone matrix.

Imbalance of bone homeostasis impairs bone remodeling

Figure 2: Illustration of the bone remodeling process

Bone homeostasis is primarily controlled by the bone remodeling process. This ensures equal amounts of resorbed and formed bone. Continuous imbalance between these may result in or be a result of the development of diseases like osteoporosis or osteosarcoma. Mature osteoclasts and osteoblasts dominate the resorption and formation of bone respectively. Over- or under-activation of either would result in imbalance of the bone homeostasis.

Many disorders with connection to an impaired bone remodeling is already identified. However, little is known about the specific mechanisms behind the development of the disorders as well as therapeutic possibilities. One of the major barriers to getting the much-needed answers to bone diseases. The treatment hereof is the huge gap between in vitro research using traditional cell culturing and in vivo studies. This ultimately leads to a prolonged shift from preliminary in vitro testing to pre-clinical tests and drugs trials. By using a relevant, reliable, and scalable in vitro system which is easily transferable to in vivo settings this gap can be lessened – all for the benefit of future patients.

Learn more about our in vitro bone models HERE

References

1. Florencio-Silva, R., et al., Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. Biomed Res Int, 2015. 2015: p. 421746.

2. Viguet-Carrin, S., P. Garnero, and P.D. Delmas, The role of collagen in bone strength. Osteoporos Int, 2006. 17(3): p. 319-36.

3. Grabowski, P., Physiology of bone. Endocr Dev, 2009. 16: p. 32-48.

4. Raggatt, L.J. and N.C. Partridge, Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(33): p. 25103-8.

5. Roodman, G.D., Mechanisms of bone metastasis. N Engl J Med, 2004. 350(16): p. 1655-64.

6. Seeman, E. and P.D. Delmas, Bone quality–the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N Engl J Med, 2006. 354(21): p. 2250-61.

7. Kenkre, J.S. and J. Bassett, The bone remodelling cycle. Ann Clin Biochem, 2018. 55(3): p. 308-327.

8. Maurizi, A. and N. Rucci, The Osteoclast in Bone Metastasis: Player and Target. Cancers (Basel), 2018. 10(7).

9. Xiao, W., et al., Cellular and Molecular Aspects of Bone Remodeling. Front Oral Biol, 2016. 18: p. 9-16.

10. Arias, C.F., et al., Bone remodeling: A tissue-level process emerging from cell-level molecular algorithms. PLoS One, 2018. 13(9): p. e0204171.

11. Delaisse, J.M., et al., Re-thinking the bone remodeling cycle mechanism and the origin of bone loss. Bone, 2020. 141: p. 115628.

12. Hadjidakis, D.J. and Androulakis, II, Bone remodeling. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2006. 1092: p. 385-96.